When the mirror cracks from side to side.

::We are continuing our dive into Tennyson, which we started last week.::

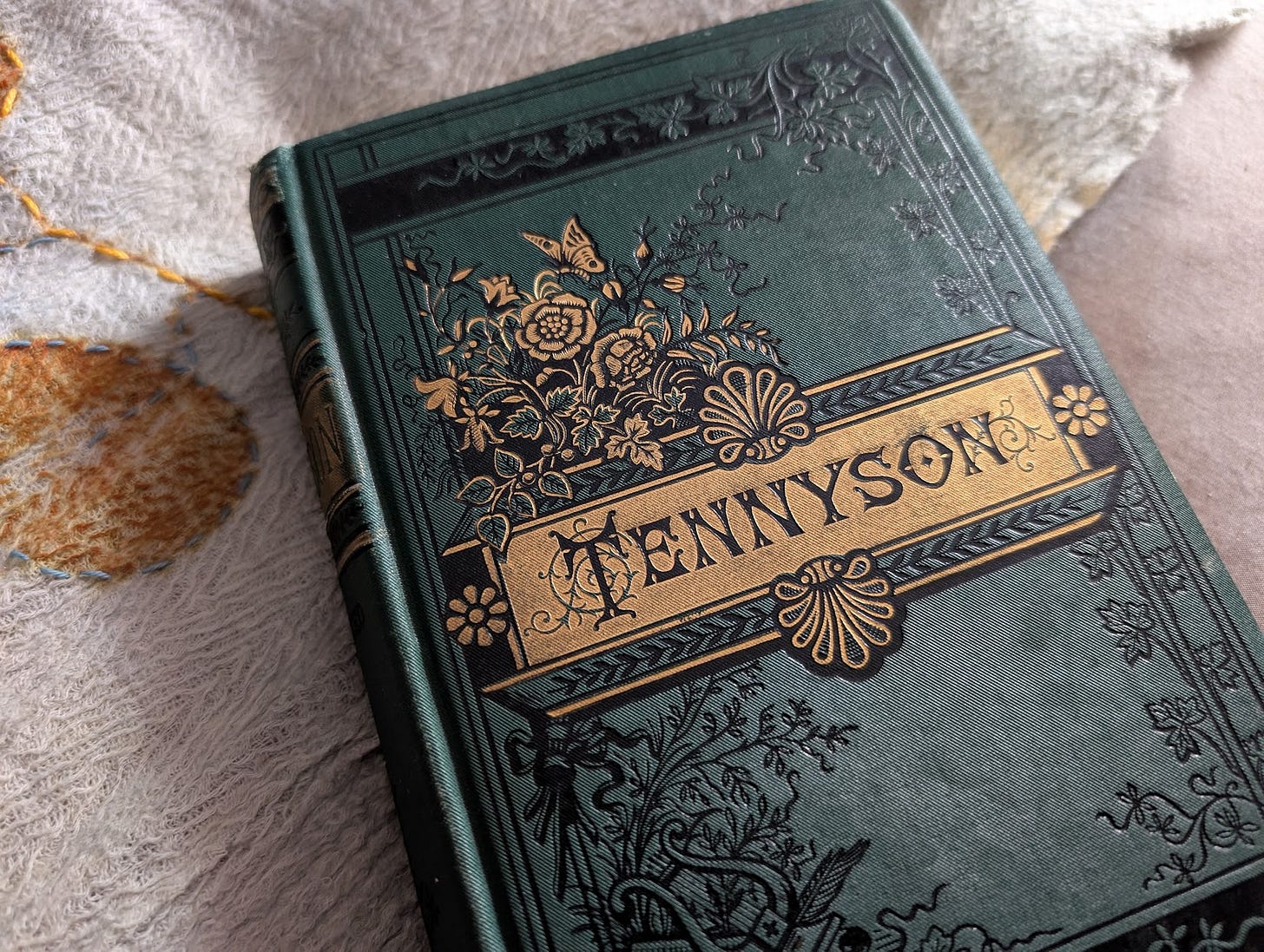

My Great-Grandmother’s book of Tennyson poems is as an object of beauty on its own, what’s known as, according to a few book sellers, a “red-line” edition due to the red border on the pages of tiny-print poetry.

I quickly found my wa…