Exiting or existing in no-man's land.

Between Christmas and the New Year, and also large chunks of your life.

It starts by assuming the land’s gender.

All is not quiet on the Western Front. The silence before it all lets loose is very loud with dread.

A no-mans-land is a place that exists but cannot be entered.

In Verdun, France, the WWI no-man’s land still exists, a toxic region called the Zone Rouge—similar to what this nation’s elites in the cities on the coast likely consider fly-over country—in which people are still forbidden to enter because of unexploded ordnance and chemical toxins.

In Cyprus, the United Nations thoughtfully created a buffer zone in which the nations are not united. A “Green Line” separates the Greeks from the Turks. Nicosia is a city, unfortunately, cleaved, a Solomonic approach to justice.

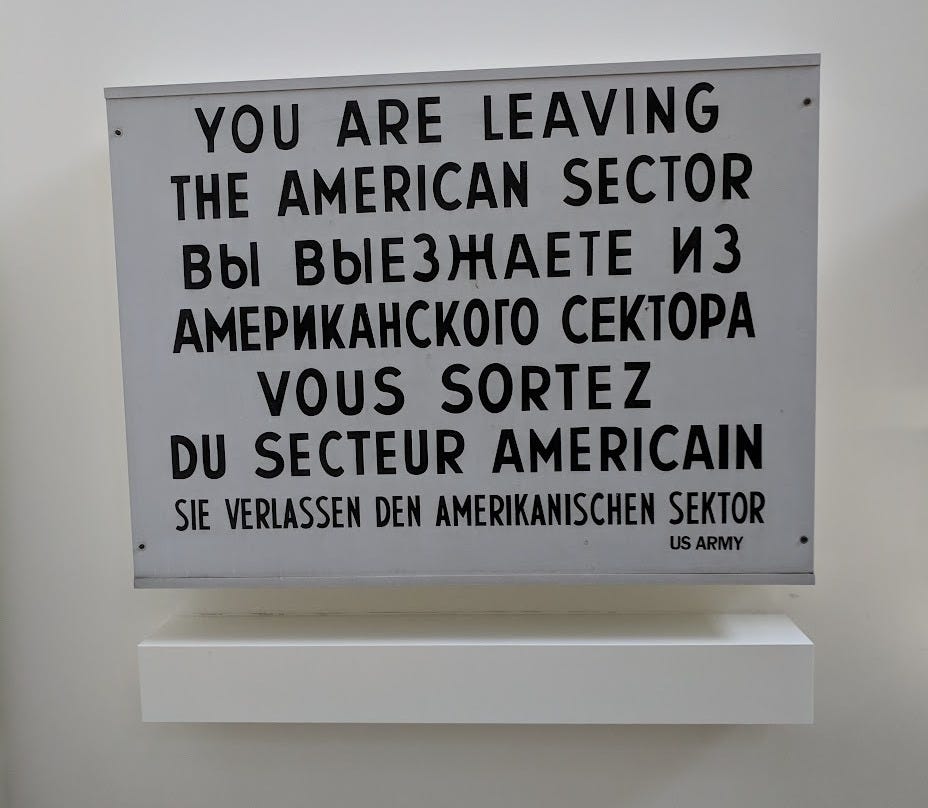

Hard to imagine today, but Berlin, too, was a city divided. The central “Death Strip” that fleshed out the Iron Curtain in the form of the Berlin Wall divided freedom and communism and insisted, despite the behavior of people fleeing from the latter to the former like a high pressure system into low, that all were equally provided for and the barbed-wire ringed Utopia with guard towers, mines, trip-wires, and horrific stories did not conflict with this. The most famous section of this bloody crossing was near Checkpoint Charlie.

In 1992, I visited Germany and saw Checkpoint Charlie. Somewhere somewhat lost in a box sit my faded Kodak photographs of the infamous checkpoint, but at least, being an American, I got the t-shirt and I still have it. Now you can visit that checkpoint safely in a museum, tastefully displayed, without the rotting body of Peter Fechter nearby.

Most know of the ironically named Korean Demilitarized Zone, one of the most military-intense places on the planet. The mine-filled 1.2-mile-wide DMZ cuts the Korean peninsula in half, dividing it into a southern modern nation of light and life, and a northern nation of starvation courtesy of a chubby dear leader.

Chernobyl and Fukushima have become exclusion and no-go zones, not due to war but fascination with the most energy-dense fuel and an assumption that we can split the atom in a controlled way, with a periodic reminder otherwise. Enter these no-man’s lands at your own risk or, if you are Putin, with drones and pasty-white psychopathy.

Strange things happen in no-man’s lands.

They become nature preserves, where things grow wild. They become graves where wandering people go to die. They become points of friction and focus. They become symbols of revolution or reminders of war. They remind us that no one is in control when everyone wants to be. There is smuggling and secretive behavior.

There is another no-man’s land that I’ve come to know in life. Several, in fact, but the shortest one is the period between Christmas and the New Year. While I know some will insist Christmas is twelve days, and that massive amounts of birds and leaping lords are appropriate gifts until January 6, we all know it is not.

What are you supposed to do in this awkward week sandwich in which all expectations hang and will soon fizzle out when credit card bills and week two of the gym arrive?

Years ago, when I was young, I decided to ring in the New Year by banging kettle lids together in the kitchen and yelling Happy New Year. My mother came flying out of the bedroom in her nightie, Dad’s voice hollering after her, and I assure you that while it was a quick exit from the no-man’s land, it was not a happy start to the new year.

In recent memory, happiness has little to do with a new year. Apathy is more at home, even as we find ways to cope with the expectation to demarcate the new calendar. I confess that even though I used to be known as the “Christmas kid” for my love of Christmas, I suggested we didn’t even put up a tree this year. “We’ll only have to take it down,” I said, unwilling to also debate this point on washing dishes, clothes, and other Sisyphean tasks.

Perhaps 2022 was the last year I felt something at this point on the calendar. I don’t care to explain why, mostly because I don’t know, other than roundabout discussions of the road signs along what has been several years of unpleasant internal journey, in which I wonder why I keep trying to start the engine yet again.

Tonight, we are going to Mandan, North Dakota, and watch as they attempt to blow themselves off the map—perhaps into a no-man’s land—and break some kind of world record for most Roman candle fireworks. There is a natural draw to see such a spectacle, but if over two million explosions to end the year cannot wake me from the funk, I guess I don’t know what to say.

Whole entire sections and years of life can feel like a no-man’s land, a place you wandered into that you weren’t supposed to. Who knew it existed, tucked between assumptions and dreams? It’s a place of confusion, where you’re not sure who has control, where weeds and wild things take root, where dreams and ideas and feelings go to die.

If you have not stumbled into it, I assure you that your time is coming. Time is the most brutal of dimensions, though width is a close second. Everyone tells you about bad knees and eyes and the joy of “doctoring” as you age, but they don’t tell you about time manipulation.

At least for me, the older I get, the stranger time has moved.

I can’t tell if I’ve somehow mastered time and made it insubstantial, dabbling my toes towards eternity, or if I’m about to get flung off the merry-go-round. Past things are weaving into the present at an alarming rate, bringing both better understanding and abject frustration, and in some moments, I feel as if I’m shifting across time. Changes happen so gradually that they feel sudden; it takes me so long to arrive at that moment of noticing. Weeks and months pass in a fog of focus on productivity and routine and the lost meaning of life, that mechanism that allows gradual changes to pounce, as when someone you love dies (or nearly so), or an event somehow shatters your life.

There is a sense that I’m existing at the periphery. Riding in a car and 200 miles magically erased from memory, or an hour gone from the clock, lost in thoughts that, if not written down, are quickly gone as well. Time is exchanged for the ephemeral. Walking through a store or in a group of people and feeling mechanically there but not really, desperately trying to be Teddy Roosevelt’s man in the arena—or even a spectator in the arena—but feeling more like the Goodyear blimp passing silently overhead.

I thought of these things last night while I was staring at my face in the mirror for two minutes, noting the Polish sag of my chubby cheeks, the gray hair, tired eyes, deep furrow by one brow, and wondering just a general why (and maybe a when). I dreaded the looming-but-immediate dwindling hope that maybe this is the year, for what I don’t know, and wondering why that hope won’t just shut up because I already know time is going to mess with me in no-man’s land, which has become an almost-senior-citizen version of A Wrinkle In Time.

That mirror version is not the person I think of when I think of myself. I don’t recognize her life.

It hurt, so I came back to the present, back to reality, and leaned down to spit into the sink and wondered why Listerine hated people so much.